I am accepting charitable donations,.

ETH: ENS: REBILAC.XYZ | BTC: OPENSEA TREASURE | xDAI: ENS: REBILAC.XYZ

I. J. Good

| I. J. Good | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Isadore Jacob Gudak 9 December 1916 London, UK |

| Died | 5 April 2009 (aged 92) Radford, Virginia, US |

| Alma mater | Jesus College, Cambridge |

| Awards | Smith's Prize (1940) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Statistician, cryptologist |

| Institutions | Trinity College, Oxford; Virginia Tech |

| Doctoral advisor | G. H. Hardy |

Irving John ("I. J."; "Jack") Good (9 December 1916 – 5 April 2009)[1][2] was a British mathematician who worked as a cryptologist at Bletchley Park with Alan Turing. After World War II, Good continued to work with Turing on the design of computers and Bayesian statistics at the University of Manchester. Good moved to the United States where he was professor at Virginia Tech.

He was born Isadore Jacob Gudak to a Polish Jewish family in London. He later anglicised his name to Irving John Good and signed his publications "I. J. Good."

An originator of the concept now known as "intelligence explosion," Good served as consultant on supercomputers to Stanley Kubrick, director of the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey.[3]

Life[edit]

Good was born Isadore Jacob Gudak to Polish Jewish parents in London. His father was a watchmaker, who later managed and owned a successful fashionable jewellery shop, and was also a notable Yiddish writer writing under the pen-name of Moshe Oved. Good was educated at the Haberdashers' Aske's Boys' School, at the time in Hampstead in north west London, where, Dan van der Vat writes, Good effortlessly outpaced the mathematics curriculum.[3]

Good studied mathematics at Jesus College, Cambridge, graduating in 1938 and winning the Smith's Prize in 1940.[4] He did research under G.H. Hardy and Besicovitch before moving to Bletchley Park in 1941 on completing his doctorate.

Bletchley Park[edit]

On 27 May 1941, having just obtained his doctorate at Cambridge, Good walked into Hut 8, Bletchley's facility for breaking German naval ciphers, for his first shift. This was the day that Britain's Royal Navy destroyed the German battleship Bismarck after it had sunk the Royal Navy's HMS Hood. Bletchley had contributed to Bismarck's destruction by discovering, through wireless-traffic analysis, that the German flagship was sailing for Brest, France, rather than Wilhelmshaven, from which she had set out.[3] Hut 8 had not, however, been able to decrypt on a current basis the 22 German Naval Enigma messages that had been sent to Bismarck. The German Navy's Enigma ciphers were considerably more secure than those of the German Army or Air Force, which had been well penetrated by 1940. Naval messages were taking three to seven days to decrypt, which usually made them operationally useless for the British. This was about to change, however, with Good's help.[3]

Alan Turing... had caught Good sleeping on the floor while on duty during his first night shift. At first, Turing thought Good was ill, but he was cross when Good explained that he was just taking a short nap because he was tired. For days afterwards, Turing would not deign to speak to Good, and he left the room if Good walked in. The new recruit only won Turing's respect after he solved the bigram tables problem. During a subsequent night shift, when there was no more work to be done, it dawned on Good that there might be another chink in the German indicating system. The German telegraphists had to add dummy letters to the trigrams which they selected out of the kenngruppenbuch... Good wondered if their choice of dummy letters was random, or whether there was a bias towards particular letters. After inspecting some messages which had been broken, he discovered that there was a tendency to use some letters more than others. That being the case, all the codebreakers had to do, was to work back from the indicators given at the beginning of each message, and apply each bigram table in turn in the same way as Joan Clarke had done before. The bigram table which produced one of the popular dummy letters was probably the correct one. When Good mentioned his discovery to Alan Turing, Turing was very embarrassed, and said, 'I could have sworn that I tried that.' It quickly became an important part of the Banburismus procedure.

Jack Good's refusal to go on working when tired was vindicated by a subsequent incident. During another long night shift, he had been baffled by his failure to break a doubly enciphered Offizier message. This was one of the messages which was supposed to be enciphered initially with the Enigma set up in accordance with the Offizier settings, and subsequently with the general Enigma settings in place. However, while he was sleeping before returning for another shift, he dreamed that the order had been reversed; the general settings had been applied before the Offizier settings. Next day he found that the message had yet to be read, so he applied the theory which had come to him during the night. It worked; he had broken the code in his sleep.[5]

Good served with Turing for nearly two years.[3]

Subsequently, he worked with Donald Michie in Max Newman's group on the Fish ciphers, leading to the development of the Colossus computer.

Good was a member of the Bletchley Chess Club which defeated the Oxford University Chess Club 8–4 in a twelve-board team match held on 2 December 1944. Good played fourth board for Bletchley Park, with C.H.O'D. Alexander, Harry Golombek, and James Macrae Aitken in the top three spots.[6] He won his game against Sir Robert Robinson.[7]

Postwar work[edit]

In 1947 Newman invited Good to join him and Turing at Manchester University. There for three years Good lectured in mathematics and researched computers, including the Manchester Mark 1.[3]

In 1948 Good was recruited by the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), successor to Bletchley Park. He remained there until 1959, while also taking up a brief associate professorship at Princeton University and a short consultancy with IBM.[3]

From 1959 until he moved to the US in 1967, Good held government-funded positions and from 1964 a senior research fellowship at Trinity College, Oxford, and the Atlas Computer Laboratory, where he continued his interests in computing, statistics and chess.[2] He later left Oxford, declaring it "a little stiff".

United States[edit]

In 1967 Good moved to the United States, where he was appointed a research professor of statistics at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. In 1969 he was appointed a University Distinguished Professor at Virginia Tech, and in 1994 Emeritus University Distinguished Professor.[8] In 1973 he was elected as a Fellow of the American Statistical Association.[9]

He later said about his arrival in Virginia (from England) in 1967 to start teaching at VPI, where he taught from 1967 to 1994:

"I arrived in Blacksburg in the seventh hour of the seventh day of the seventh month of the year seven in the seventh decade, and I was put in Apartment 7 of Block 7...all by chance."[10]

Research and publications[edit]

Good's published work ran to over three million words.[3] He was known for his work on Bayesian statistics. He published a number of books on probability theory. In 1958 he published an early version of what later became known as the fast Fourier transform[11] but it did not became widely known. He played chess to county standard and helped popularise Go, an Asian boardgame, through a 1965 article in New Scientist (he had learned the rules from Alan Turing).[12] In 1965 he originated the concept now known as "intelligence explosion," which anticipates the eventual advent of superhuman intelligence:

Let an ultraintelligent machine be defined as a machine that can far surpass all the intellectual activities of any man however clever. Since the design of machines is one of these intellectual activities, an ultraintelligent machine could design even better machines; there would then unquestionably be an 'intelligence explosion,' and the intelligence of man would be left far behind. Thus the first ultraintelligent machine is the last invention that man need ever make, provided that the machine is docile enough to tell us how to keep it under control.[13]

Good's authorship of treatises such as "Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine" and "Logic of Man and Machine" (both 1965) made him the obvious person for Stanley Kubrick to consult when filming 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), one of whose principal characters was the paranoid HAL 9000 supercomputer.[3] In 1995 Good was elected a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.[2]

According to his assistant, Leslie Pendleton, in 1998 Good wrote in an unpublished autobiographical statement that he suspected an ultraintelligent machine would lead to the extinction of man.[14]

Personality[edit]

The slender, bushy-moustached Good was blessed with a sense of humour. He published a paper under the names IJ Good and "K Caj Doog"—the latter, his own nickname spelled backwards. In a 1988 paper,[15] he introduced its subject by saying, "Many people have contributed to this topic but I shall mainly review the writings of I. J. Good because I have read them all carefully." In Virginia he chose, as his vanity license plate, "007IJG," in subtle reference to his World War II intelligence work.[3]

Good never married.[16] After going through ten assistants in his first thirteen years at Virginia, he hired Leslie Pendleton, who proved up to the task of managing his quirks. He wanted to marry her, but she refused. Although there was speculation, they were never more than friends, but she was his assistant, companion, and friend for the rest of his life.[17]

Death[edit]

Good died on 5 April 2009 of natural causes in Radford, Virginia, aged 92.[18]

Books[edit]

- Good, I.J. (1950), Probability and the Weighing of Evidence, London: Griffin, ASIN B0000CHL1R

- Good, Irving John (1965), The estimation of probabilities: An essay on modern Bayesian methods, Research monograph no. 30, M.I.T. Press, ASIN B0006BMRMM

- Good, Irving John (1965), The scientist speculates: An anthology of partly-baked ideas, Capricorn Books

- Osteyee, David Bridston; Good, Irving John (1974), Information, Weight of Evidence: The Singularity Between Probability Measures and Signal Detection, Springer, ISBN 978-3-540-06726-9

- Good, Irving John (2009) [1983], Good Thinking: The Foundations of Probability and Its Applications, of Minnesota Press (Republished by Dover), ISBN 978-0486474380

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ "Passings". Los Angeles Times. 13 April 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2009.

- ^ a b c The Times of 16-apr-09, http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/obituaries/article6100314.ece (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dan van der Vat (29 April 2009), "Jack Good" (obituary), The Guardian, p. 32, retrieved 9 October 2013

- ^ Appendix to Barrow-Green, June. "'A corrective to the spirit of too exclusively pure mathematics': Robert Smith (1689-1768) and his prizes at Cambridge University." Annals of science 56.3 (1999): 271-316.

- ^ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Enigma: The Battle for the Code, p. 189.

- ^ Chess Notes 4034. The code-breakers by Edward Winter; based on a report from CHESS, February 1945, p. 73.

- ^ British Chess magazine, February 1945, p36

- ^ "Good, Irving John", CV, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 6 April 2009, retrieved 9 April 2017

- ^ View/Search Fellows of the ASA, accessed 2016-08-20.

- ^ Salsburg, David (2002), The Lady Tasting Tea: How Statistics Revolutionized Science in the Twentieth Century, Macmillan, p. 222, ISBN 9781466801783.

- ^ "The interaction algorithm and practical fourier analysis," Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 361–372, 1958, addendum: ibid. 22 (2), 373–375 (1960).

- ^ "The mystery of Go", The New Scientist, January 1965, pp. 172–74.

- ^ I.J. Good, "Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine" Archived 28 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine. (HTML), Advances in Computers, vol. 6, 1965.

- ^ Barrat, James (2013). Our final invention : artificial intelligence and the end of the human era (First ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312622374.

In the bio, playfully written in the third person, Good summarized his life’s milestones, including a probably never before seen account of his work at Bletchley Park with Turing. But here’s what he wrote in 1998 about the first superintelligence, and his late-in-the-game U-turn: [The paper] 'Speculations Concerning the First Ultra-intelligent Machine' (1965) . . . began: 'The survival of man depends on the early construction of an ultra-intelligent machine.' Those were his [Good’s] words during the Cold War, and he now suspects that 'survival' should be replaced by 'extinction.' He thinks that, because of international competition, we cannot prevent the machines from taking over. He thinks we are lemmings. He said also that 'probably Man will construct the deus ex machina in his own image.'

- ^ I.J. Good, "The Interface Between Statistics and Philosophy of Science," Statistical Science, vol. 3, no. 4, 1988, pp. 386–97.

- ^ http://www.vtnews.vt.edu/story.php?relyear=2009&itemno=276

- ^ http://io9.com/why-a-superintelligent-machine-may-be-the-last-thing-we-1440091472

- ^ Virginia Tech news release of Good's death.

References[edit]

- Dan van der Vat, "Jack Good" (obituary), The Guardian, 29 April 2009, p. 32.

- Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, Enigma: The Battle for the Code, London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2000, ISBN 978-0-297-84251-4.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: I. J. Good |

- I. J. Good at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Good's web page at Virginia Tech

- Bibliography ("Shorter Publications List", running to 2300 items) (PDF)

- Biography focusing on Good's role in the history of computing

- Project Euclid An interview with Good can be downloaded from here

- VT Image Base Photographs

- Obituary, Virginia Tech, 6 April 2009

- Obituary, Daily Telegraph, 10 April 2009

- Obituary, The Times, 16 April 2009

- Obituary, The Independent, 14 May 2009

- Eulogy Mathematical eulogy (with Maple code) by Doron Zeilberger, 2 December 2009

- 1916 births

- 2009 deaths

- 20th-century American mathematicians

- 21st-century American mathematicians

- 20th-century American philosophers

- Alan Turing

- Alumni of Jesus College, Cambridge

- American people of British-Jewish descent

- American people of Polish-Jewish descent

- American statisticians

- Artificial intelligence researchers

- Bayesian statisticians

- British cryptographers

- British information theorists

- British Jews

- British people of Polish-Jewish descent

- Disease-related deaths in Virginia

- English emigrants to the United States

- English Jews

- English mathematicians

- English statisticians

- Fellows of the American Statistical Association

- Government Communications Headquarters people

- Modern cryptographers

- People associated with Bletchley Park

- People educated at Haberdashers' Aske's Boys' School

- People from Hampstead

- People from Radford, Virginia

- Singularitarianism

- Theoretical computer scientists

- Amateur chess players

- Foreign Office personnel of World War II

Isaac

| Isaac | |

|---|---|

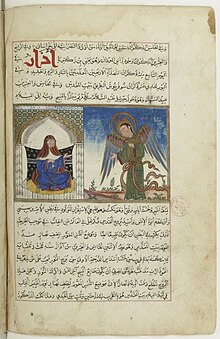

Isaac digging for the wells, imagined in a Bible illustration (c. 1900)

|

|

| Personal | |

| Born | Canaan |

| Died | Canaan |

| Spouse | Rebecca |

| Children | Esau Jacob |

According to the biblical Book of Genesis, Isaac (/ˈaɪzək/; Hebrew: יִצְחָק, Modern Yiṣḥáq Tiberian Yiṣḥāq; Arabic: إسحٰق/إسحاق, Isḥāq) was the son of Abraham and Sarah and father of Jacob; his name means "he will laugh", reflecting Sarah's response when told that she would have a child.[1] In the Bible, he is one of the three patriarchs of the Israelites, the only one whose name was not changed, and the only one who did not move out of Canaan.[1] According to the narrative, he died when he was 180 years old, the longest-lived of the three.[1]

The biblical narrative of Isaac has influenced various religious traditions, including Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Modern scholarship doubts the existence of figures from Genesis, including Isaac.[2]

Etymology[edit]

The anglicized name Isaac is a transliteration of the Hebrew term Yiṣḥāq which literally means "He laughs/will laugh."[3] Ugaritic texts dating from the 13th century BCE refer to the benevolent smile of the Canaanite deity El.[4] Genesis, however, ascribes the laughter to Isaac's parents, Abraham and Sarah, rather than El. According to the biblical narrative, Abraham fell on his face and laughed when God (Hebrew, Elohim) imparted the news of their son's eventual birth. He laughed because Sarah was past the age of childbearing; both she and Abraham were advanced in age. Later, when Sarah overheard three messengers of the Lord renew the promise, she laughed inwardly for the same reason. Sarah denied laughing when God questioned Abraham about it.[5][6][7]

Genesis narrative[edit]

Birth[edit]

It was prophesied to the patriarch Abraham that he would have a son and that his name should be Isaac. When Abraham became one hundred years old, this son was born to him by his first wife Sarah.[8] Though this was Abraham's second son[9] it was Sarah's first and only child.

On the eighth day from his birth, Isaac was circumcised, as was necessary for all males of Abraham's household, in order to be in compliance with Yahweh's covenant.[10]

After Isaac had been weaned, Sarah saw Ishmael mocking, and urged her husband to cast out Hagar the bondservant and her son, so that Isaac would be Abraham's sole heir. Abraham was hesitant, but at God's order he listened to his wife's request.[11]

Binding[edit]

At some point in Isaac's youth, his father Abraham brought him to Mount Moriah. At God's command, Abraham was to build a sacrificial altar and sacrifice his son Isaac upon it. After he had bound his son to the altar and drawn his knife to kill him, at the very last moment an angel of God prevented Abraham from proceeding. Rather, he was directed to sacrifice instead a nearby ram that was stuck in thickets. This event served as a test of Abraham's faith in God, [12] not as an actual human sacrifice.[13]

Family life[edit]

When Isaac was 40, Abraham sent Eliezer, his steward, into Mesopotamia to find a wife for Isaac, from his nephew Bethuel's family. Eliezer chose the Aramean Rebekah for Isaac. After many years of marriage to Isaac, Rebekah had still not given birth to a child and was believed to be barren. Isaac prayed for her and she conceived. Rebekah gave birth to twin boys, Esau and Jacob. Isaac was 60 years old when his two sons were born.[14] Isaac favored Esau, and Rebekah favored Jacob.[15]

Isaac is unique among the patriarchs for remaining faithful to his wife, and for not having concubines.[16][17]

Migration[edit]

At the age of 75, Isaac moved to Beer-lahai-roi after his father died.[18] When the land experienced famine, he removed to the Philistine land of Gerar where his father once lived. This land was still under the control of King Abimelech as it was in the days of Abraham. Like his father, Isaac also deceived Abimelech about his wife and also got into the well business. He had gone back to all of the wells that his father dug and saw that they were all stopped up with earth. The Philistines did this after Abraham died. So, Isaac unearthed them and began to dig for more wells all the way to Beersheba, where he made a pact with Abimelech, just like in the day of his father.[19]

Birthright[edit]

Isaac grew old and became blind. He called his son Esau and directed him to procure some venison for him, in order to receive Isaac's blessing. While Esau was hunting, Jacob, after listening to his mother's advice, deceived his blind father by misrepresenting himself as Esau and thereby obtained his father's blessing, such that Jacob became Isaac's primary heir and Esau was left in an inferior position. According to Genesis 25:29–34, Esau had previously sold his birthright to Jacob for "bread and stew of lentils". Thereafter, Isaac sent Jacob into Mesopotamia to take a wife of his mother's brother's house. After 20 years working for his uncle Laban, Jacob returned home. He reconciled with his twin brother Esau, then he and Esau buried their father, Isaac, in Hebron after he died at the age of 180.[20][21]

Family tree[edit]

| Terah | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sarah[22] | Abraham | Hagar | Haran | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nahor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ishmael | Milcah | Lot | Iscah | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ishmaelites | 7 sons[23] | Bethuel | 1st daughter | 2nd daughter | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isaac | Rebecca | Laban | Moabites | Ammonites | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Esau | Jacob | Rachel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bilhah | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Edomites | Zilpah | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leah | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Reuben 2. Simeon 3. Levi 4. Judah 9. Issachar 10. Zebulun Dinah (daughter) |

7. Gad 8. Asher |

5. Dan 6. Naphtali |

11. Joseph 12. Benjamin |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Burial site[edit]

According to local tradition, the graves of Isaac and Rebekah, along with the graves of Abraham and Sarah and Jacob and Leah, are in the Cave of the Patriarchs.

Jewish views[edit]

In rabbinical tradition, the age of Isaac at the time of binding is taken to be 37, which contrasts with common portrayals of Isaac as a child.[24] The rabbis also thought that the reason for the death of Sarah was the news of the intended sacrifice of Isaac.[24] The sacrifice of Isaac is cited in appeals for the mercy of God in later Jewish traditions.[25] The post-biblical Jewish interpretations often elaborate the role of Isaac beyond the biblical description and primarily focus on Abraham's intended sacrifice of Isaac, called the aqedah ("binding").[4] According to a version of these interpretations, Isaac died in the sacrifice and was revived.[4] According to many accounts of Aggadah, unlike the Bible, it is Satan who is testing Isaac as an agent of God.[26] Isaac's willingness to follow God's command at the cost of his death has been a model for many Jews who preferred martyrdom to violation of the Jewish law.[24]

According to the Jewish tradition, Isaac instituted the afternoon prayer. This tradition is based on Genesis chapter 24, verse 63[27] ("Isaac went out to meditate in the field at the eventide").[24]

Isaac was the only patriarch who stayed in Canaan during his whole life and though once he tried to leave, God told him not to do so.[28] Rabbinic tradition gave the explanation that Isaac was almost sacrificed and anything dedicated as a sacrifice may not leave the Land of Israel.[24] Isaac was the oldest of the biblical patriarchs at the time of his death, and the only patriarch whose name was not changed.[4][29]

Rabbinic literature also linked Isaac's blindness in old age, as stated in the Bible, to the sacrificial binding: Isaac's eyes went blind because the tears of angels present at the time of his sacrifice fell on Isaac's eyes.[26]

Christian views[edit]

The early Christian church continued and developed the New Testament theme of Isaac as a type of Christ and the Church being both "the son of the promise" and the "father of the faithful". Tertullian draws a parallel between Isaac's bearing the wood for the sacrificial fire with Christ's carrying his cross.[30] and there was a general agreement that, while all the sacrifices of the Old Law were anticipations of that on Calvary, the sacrifice of Isaac was so "in a pre-eminent way".[31]

The Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church consider Isaac as a Saint along with other biblical patriarchs.[32] Along with those of other patriarchs and the Old Testament Righteous, his feast day is celebrated in the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Byzantine rite of the Catholic Church on the Second Sunday before Christmas (December 11–17), under the title the Sunday of the Forefathers.[33][34]

New Testament[edit]

The New Testament states Isaac was "offered up" by his father Abraham, and that Isaac blessed his sons.[29] Paul contrasted Isaac, symbolizing Christian liberty, with the rejected older son Ishmael, symbolizing slavery;[4][35] Hagar is associated with the Sinai covenant, while Sarah is associated with the covenant of grace, into which her son Isaac enters. The Epistle of James chapter 2, verses 21–24,[36] states that the sacrifice of Isaac shows that justification (in the Johannine sense) requires both faith and works.[37]

In the Epistle to the Hebrews, Abraham's willingness to follow God's command to sacrifice Isaac is used as an example of faith as is Isaac's action in blessing Jacob and Esau with reference to the future promised by God to Abraham[38] In verse 19, the author views the release of Isaac from sacrifice as analogous to the resurrection of Jesus, the idea of the sacrifice of Isaac being a prefigure of the sacrifice of Jesus on the cross.[39]

Islamic views[edit]

Islam considers Isaac as a prophet of Islam, and describes him as the father of the Israelites and a righteous servant of God.

Isaac, along with Ishmael, is highly important for Muslims for continuing to preach the message of monotheism after his father Abraham. Among Isaac's children was the follow-up Israelite patriarch Jacob, who too is venerated an Islamic prophet.

Isaac is mentioned fifteen times by name in the Quran, often with his father and his son, Jacob.[40] The Quran states that Abraham received "good tidings of Isaac, a prophet, of the righteous", and that God blessed them both (37: 12). In a fuller description, when angels came to Abraham to tell him of the future punishment to be imposed on Sodom and Gomorrah, his wife, Sarah, "laughed, and We gave her good tidings of Isaac, and after Isaac of (a grandson) Jacob" (11: 71–74); and it is further explained that this event will take place despite Abraham and Sarah's old age. Several verses speak of Isaac as a "gift" to Abraham (6: 84; 14: 49–50), and 24: 26–27 adds that God made "prophethood and the Book to be among his offspring", which has been interpreted to refer to Abraham's two prophetic sons, his prophetic grandson Jacob, and his prophetic great-grandson Joseph. In the Qur'an, it later narrates that Abraham also praised God for giving him Ishmael and Isaac in his old age (14: 39–41).

Elsewhere in the Quran, Isaac is mentioned in lists: Joseph follows the religion of his forefathers Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (12: 38) and speaks of God's favor to them (12: 6); Jacob's sons all testify their faith and promise to worship the God that their forefathers, "Abraham, Ishmael and Isaac", worshiped (2: 127); and the Qur'an commands Muslims to believe in the revelations that were given to "Abraham, Ishmael, Isaac, Jacob and the Patriarchs" (2: 136; 3: 84). In the Quran's narrative of Abraham's near-sacrifice of his son (37: 102), the name of the son is not mentioned and debate has continued over the son's identity, though many feel that the identity is the least important element in a story which is given to show the courage that one develops through faith.[41]

Quran[edit]

The Quran mentions Isaac as a prophet and a righteous man of God. Isaac and Jacob are mentioned as being bestowed upon Abraham as gifts of God, who then worshipped God only and were righteous leaders in the way of God:

And We bestowed on him Isaac and, as an additional gift, (a grandson), Jacob, and We made righteous men of every one (of them).

And We made them leaders, guiding (men) by Our Command, and We sent them inspiration to do good deeds, to establish regular prayers, and to practise regular charity; and they constantly served Us (and Us only).

And WE gave him the glad tidings of Isaac, a Prophet, and one of the righteous.

Academic[edit]

Some scholars have described Isaac as "a legendary figure" or "as a figure representing tribal history, or "as a seminomadic leader."[44] The stories of Isaac, like other patriarchal stories of Genesis, are generally believed to have "their origin in folk memories and oral traditions of the early Hebrew pastoralist experience."[45] The Cambridge Companion to the Bible makes the following comment on the biblical stories of the patriarchs:

Yet for all that these stories maintain a distance between their world and that of their time of literary growth and composition, they reflect the political realities of the later periods. Many of the narratives deal with the relationship between the ancestors and peoples who were part of Israel's political world at the time the stories began to be written down (eighth century B.C.E.). Lot is the ancestor of the Transjordanian peoples of Ammon and Moab, and Ishmael personifies the nomadic peoples known to have inhabited north Arabia, although located in the Old Testament in the Negev. Esau personifies Edom (36:1), and Laban represents the Aramean] states to Israel's north. A persistent theme is that of difference between the ancestors and the indigenous Canaanites… In fact, the theme of the differences between Judah and Israel, as personified by the ancestors, and the neighboring peoples of the time of the monarchy is pressed effectively into theological service to articulate the choosing by God of Judah and Israel to bring blessing to all peoples."[46]

According to Martin Noth, a scholar of the Hebrew Bible, the narratives of Isaac date back to an older cultural stage than that of the West-Jordanian Jacob.[44] At that era, the Israelite tribes were not yet sedentary. In the course of looking for grazing areas, they had come in contact in southern Philistia with the inhabitants of the settled countryside.[44] The biblical historian A. Jopsen believes in the connection between the Isaac traditions and the north, and in support of this theory adduces Amos 7:9 ("the high places of Isaac").[44]

Albrecht Alt and Martin Noth hold that, "The figure of Isaac was enhanced when the theme of promise, previously bound to the cults of the 'God the Fathers' was incorporated into the Israelite creed during the southern-Palestinian stage of the growth of the Pentateuch tradition."[44] According to Martin Noth, at the Southern Palestinian stage of the growth of the Pentateuch tradition, Isaac became established as one of the biblical patriarchs, but his traditions were receded in the favor of Abraham.[44]

Documentary hypothesis[edit]

Form critics variously assign passages like Genesis chapter 26, verses 6–11, to the Jahwist source, and Genesis chapter 20 verses 1–7, chapter 21, verse 1 to chapter 22, verse 14 and chapter 22, verse 19 to the Elohist. According to the compilation hypothesis, the formulaic use of the word toledoth (generations) indicates that Genesis chapter 11, verse 27 to chapter 25, verse 19 is Isaac's record through Abraham's death (with Ishmael's record appended), and Genesis chapter 25, verse 19 to chapter 37, verse 2 is Jacob's record through Isaac's death (with Esau's records appended).[47]

In art[edit]

The earliest Christian portrayal of Isaac is found in the Roman catacomb frescoes.[48] Excluding the fragments, Alison Moore Smith classifies these artistic works in three categories:

"Abraham leads Isaac towards the altar; or Isaac approaches with the bundle of sticks, Abraham having preceded him to the place of offering .... Abraham is upon a pedestal and Isaac stands near at hand, both figures in orant attitude .... Abraham is shown about to sacrifice Isaac while the latter stands or kneels on the ground beside the altar. Sometimes Abraham grasps Isaac by the hair. Occasionally the ram is added to the scene and in the later paintings the Hand of God emerges from above."[48]

See also[edit]

- Biblical narratives and the Qur'an

- Testament of Isaac

- Wife–sister narratives in the Book of Genesis – three such narratives involving Abraham (two) and Isaac (one)

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c deClaise-Walford 2000, p. 647.

- ^ Craig A. Evans; Joel N. Lohr; David L. Petersen (20 March 2012). The Book of Genesis: Composition, Reception, and Interpretation. BRILL. p. 64. ISBN 90-04-22653-2.

- ^ Strong's Concordance, Strong, James, ed., Isaac, Isaac's, 3327 יִצְחָק 3446, 2464.

- ^ a b c d e Encyclopedia of Religion, Isaac.

- ^ Genesis 17:15–19 18:10–15

- ^ Singer, Isidore; Broydé, Isaac (1901–1906). "Isaac". In Singer, Isidore; Adler, Cyrus; et al. Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ Hirsch, Emil G.; Bacher, Wilhelm; Lauterbach, Jacob Zallel; Jacobs, Joseph; Montgomery, Mary W. (1901–1906). "Sarah (Sarai)". In Singer, Isidore; Adler, Cyrus; et al. Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ Genesis 18:10–12

- ^ Genesis 16:15

- ^ Genesis 21:1–5

- ^ Genesis 21:8–12

- ^ Hebrews 11:17

- ^ Genesis 22

- ^ Genesis 25:26

- ^ Genesis 25:20–28

- ^ Title= Encyclopaedia Judaica | Volume 10 pg=34

- ^ Genesis 35:22

- ^ Genesis 25:11

- ^ Genesis 26

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia, Isaac.

- ^ Genesis 35:28–29

- ^ Genesis 20:12: Sarah was the half–sister of Abraham.

- ^ Genesis 22:21-22: Uz, Buz, Kemuel, Chesed, Hazo, Pildash, and Jidlaph

- ^ a b c d e The New Encyclopedia of Judaism, Isaac.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Isaac.

- ^ a b Brock, Sebastian P., Brill's New Pauly, Isaac.

- ^ Genesis 24:63

- ^ Genesis 26:2

- ^ a b Easton, M. G., Illustrated Bible Dictionary, 3rd ed., Isaac.

- ^ Cross and Livingstone, Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 1974, art Isaac

- ^ Kelly, J.N.D. Early Christian Doctrines, A & C Black, 1965. p. 72

- ^ The patriarchs, prophets and certain other Old Testament figures have been and always will be honored as saints in all the Church's liturgical traditions. – Catechism of the Catholic Church 61

- ^ http://orthodoxwiki.org/Sunday_of_the_Forefathers

- ^ Liturgy > Liturgical year >The Christmas Fast – Byzantine Catholic Archeparchy of Pittsburgh

- ^ Galatians 4:21–31

- ^ James 2:21–24

- ^ Encyclopedia of Christianity, Bowden, John, ed., Isaac.

- ^ Hebrews 11:17–20

- ^ see F.F. Bruce, The Epistle to the Hebrews Marshall. Morgan and Scott, 1964 pp. 308–13 for all this paragraph.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam, W. Montgomery Watt, Isaac

- ^ Concise Encyclopedia of Islam, C. Glasse, Isaac

- ^ Quran 21:72

- ^ Quran 37:112

- ^ a b c d e f Eerdmans Encyclopedia of Christianity, Isaac, p. 744.

- ^ Columbia Encyclopedia, Isaac.

- ^ The Cambridge Companion to the Bible, p. 59.

- ^ Morris, Henry M. (1976). The Genesis Record: A Scientific and Devotional Commentary on the Book of Beginnings. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House. pp. 26–30. ISBN 0-8010-6004-4.

- ^ a b Smith, Alison Moore (1922). "The Iconography of the Sacrifice of Isaac in Early Christian Art". American Journal of Archaeology. 26 (2): 159–73. doi:10.2307/497708. JSTOR 497708.

References[edit]

- Browning, W.R.F (1996). A dictionary of the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211691-6.

- Paul Lagasse; Lora Goldman; Archie Hobson; Susan R. Norton, eds. (2000). The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). Gale Group. ISBN 978-1-59339-236-9.

- P.J. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1573-3912.

- Erwin Fahlbusch; William Geoffrey Bromiley, eds. (2001). Encyclopedia of Christianity (1st ed.). Eerdmans Publishing Company, and Brill. ISBN 0-8028-2414-5.

- John Bowden, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of Christianity (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-522393-4.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Incorporated; Rev Ed edition. 2005. ISBN 978-1-59339-236-9.

- Jane Dammen McAuliffe, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of the Qur'an. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-12356-4.

- Geoffrey Wigoder, ed. (2002). The New Encyclopedia of Judaism (2nd ed.). New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-9388-6.

- Lindsay Jones, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of Religion (2nd ed.). MacMillan Reference Books. ISBN 978-0-02-865733-2.

- deClaise-Walford, Nancy (2000). "Isaac". In David Noel Freedman; Allen C. Myers; Astrid B. Beck. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2400-4.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isaac. |

- Isaac in Jewish Encyclopedia

- Abraham's son as the intended sacrifice (Al-Dhabih, Qur'an 37:99, Qur'an 37:99–113): Issues in qur'anic exegesis, journal of Semitic Studies XXX1V/ Spring 1989

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Isaac". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Isaac". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Isaac". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Isaac". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Genesis 35:22

Jesus in Islam

| Messenger of God ʿĪsā عيسى Jesus |

|

|---|---|

The name Jesus son of Mary written in Islamic calligraphy followed by Peace be upon him

|

|

| Native name | ישוע Yēšūă‘ |

| Born | c. 7-2 BC Bethlehem, Judea, Roman Empire |

| Disappeared | c. 30-33 AD Gethsemane, Jerusalem |

| Predecessor | Yahya (John the Baptist) |

| Successor | Muhammad |

| Parent(s) | Maryam (Mary) [mother] |

| Relatives | Yahya (John the Baptist) Zakariya (Zechariah) |

| Part of a series on |

|

In Islam, ʿĪsā ibn Maryam (Arabic: عيسى بن مريم, lit. 'Jesus, son of Mary'), or Jesus, is understood to be the penultimate prophet and messenger of God (Allah) and al-Masih, the Arabic term for Messiah (Christ), sent to guide the Children of Israel (banī isrā'īl in Arabic) with a new revelation: al-Injīl (Arabic for "the Gospel").[1][2][3] Jesus is believed to be a prophet who neither married nor had any children and is reflected as a significant figure, being found in the Quran in 93 ayaat (Arabic for verses) with various titles attached such as "Son of Mary" and other relational terms, mentioned directly and indirectly, over 187 times.[2][4][5][6][6][7] Jesus is the most mentioned person in the Quran by reference; 25 times by the name Isa, third-person 48 times, first-person 35 times, and the rest as titles and attributes.[note 1][note 2][8][note 3][9]

The Quran (central religious text of Islam) and most Hadith (testimonial reports) mention Jesus to have been born a "pure boy" (without sin) to Mary (Arabic: مريم, translit. Maryam) as the result of virginal conception, similar to the event of the Annunciation in Christianity.[2][10][11] In Islamic theology, Jesus is believed to have performed many miracles, several being mentioned in the Quran such as speaking as an infant, healing various ailments such as blindness, raising the dead to life, and making birds out of clay and breathing life into them.[12] Over the centuries, Islamic writers have referenced other miracles like casting out demons, having borrowed from pre-Islamic sources, some heretical, and from canonical sources as legends about Jesus were expanded.[13] Like all prophets in Islamic thought, Jesus is also called a Muslim (i.e., one who submits to the will of God), as he preached that his followers should adopt the "straight path". Jesus is written about by some Muslim scholars as the perfect man.[14][15][16]

In Islam, Jesus is believed to have been the precursor to Muhammad, attributing the name Ahmad to someone who would follow him. Islam traditionally teaches the rejection of Jesus' divinity, that Jesus was not God incarnate, nor the Son of God, and—according to some interpretations of the Quran—the crucifixion, death and resurrection is denied and not believed to have occurred, as rather he was saved.[17] Despite the earliest Muslim traditions and exegesis quoting somewhat conflicting reports regarding a death and its length, the mainstream Muslim belief is that Jesus did not physically die, but was instead raised alive to heaven.[18][19]

Birth of Jesus[edit]

The account of Jesus begins with a prologue narrated several times in the Quran first describing the birth of his mother, Mary, and her service in the Jerusalem temple, while under the care of the prophet and priest Zechariah, who was to be the father of John the Baptist (Luke 1:5-79). The narrative has been recounted with variations and additions by Islamic historians over the centuries.

Ibn Ishaq (d. 761 or 767), an Arab historian and hagiographer, wrote the account entitled Kitab al-Mubtada (In the Beginning), reporting that Zechariah is Mary's guardian briefly, and after being incapable of maintaining her, he entrusts her to a carpenter named George. Secluded in a church, she is joined by a young man named Joseph, and they help one another fetching water and other tasks. The account of the birth of Jesus follows the Quran's narrative, adding that the birth occurred in Bethlehem beside a palm tree with a manger.[20]

At-Tabari (d. 923), a Persian scholar and historian, contributed to the Jesus' birth narrative by mentioning envoys arriving from the king of Persia with gifts (similar to the Magi from the east) for the Messiah; the command to a man called Joseph (not specifically Mary's husband) to take her and the child to Egypt and later return to Nazareth.[21]

The work The Meadows of Gold by Al-Masudi (d. 956), an Arab historian and geographer, reports Jesus being born at Bethlehem on Wednesday 24 December (a detail likely received from contemporary Christians) without mentioning the Quranic palm tree.[21]

Ali ibn al-Athir (d. 1233), an Arab or Kurdish historian and biographer, reported in The Perfection of History (al-Kamil), a work which became a standard for later Muslims, that Joseph the carpenter had a more prominent role, but is not mentioned as a relative or husband of Mary. Al-Athir writes about how Jesus as a young boy helped to detect a thief, and about bringing a boy back to life which Jesus was accused of having killed. He mentions a version of the birth narrative taking place in Egypt without mention of a manger under the palm tree, but adds that the first version of the birth in the land of Mary's people is more accurate. Al-Athir makes a point believing Mary's pregnancy to have lasted not nine or eight months, but only a single hour. His basis is that this understanding is closer to where the Quran says Mary 'conceived him and retired with him to a distant place' (19:22).[22]

Annunciation[edit]

The virgin birth of Jesus is announced to Mary by the angel Gabriel while Mary is being raised in the Temple after having been pledged to God by her mother. Gabriel states she is honored over all women of all nations and has brought her glad tidings of a holy son.[23]

A hadith narrated by Abu Hurairah, one of the earliest companions of Muhammad, quotes Muhammad:

"Hardly a single descendant of Adam is born without Satan touching him at the moment of his birth. A baby who is touched like that gives a cry. The only exceptions are Mary and her son" [cf. Q 3: 36].[24]

The angel declares the son is to be named Jesus, the Messiah, proclaiming he will be called a great prophet, being the Spirit of God and Word of God, who will receive al-Injīl (Arabic for the Gospel). The angel tells Mary that Jesus will speak in infancy, and when mature, will be a companion to the most righteous. Mary, responding how she could conceive and have a child when no man had touched her, was told by the angel that God can decree what He wills, and it shall come to pass.[25]

The conception of Jesus as described by Ibn al-Arabi (d. 1240), an Andalusian Scholar of Islam, Sufi mystic, poet and philosopher, in the Bezels of Wisdom:

From the water of Mary or from the breath of Gabriel,

- In the form of a mortal fashioned of clay,

The Spirit came into existence in an essence

- Purged of Nature's taint, which is called Sijjin (hell)

Because of this, his sojourn was prolonged,

- Enduring, by decree, more than a thousand years.

A spirit from none other than God,

- So that he might raise the dead and bring forth birds from clay.[26]

Mary, overcome by the pains of childbirth, is provided a stream of water under her feet from which she could drink and a palm tree which she could shake so ripe dates would fall and be enjoyed. As Mary carried baby Jesus back to the temple, she was asked by the temple elders about the child. Having been commanded by Gabriel to a vow of silence, she points to the infant Jesus and the infant proclaims:[27]

He said, "Lo, I am God's servant; God has given me the Book, and made me a Prophet. Blessed He has made me, wherever I may be; and He has enjoined me to pray, and to give the alms, so long as I live, and likewise to cherish my mother; He has not made me arrogant, unprosperous. Peace be upon me, the day I was born, and the day I die, and the day I am raised up alive!"[28]

Jesus speaking from the cradle is mentioned as one of six miracles in the Quran.[29] The speaking infant narrative is also found in the Syriac Infancy Gospel, a pre-Islamic sixth century work.[30]

Childhood[edit]

The narrative of fleeing from Herod continues similarly to the narrative found in the canonical Gospels and noncanonical sources, with some Islamic narratives having Jesus and family staying in Egypt for 12 years.[31] Many moral stories and miraculous events of Jesus' youth are mentioned in Qisas al-anbiya (Stories of the Prophets), books composed over the centuries about pre-Islamic prophets and heroes.[32]

Al-Masudi claims that Jesus as a boy studied the Jewish religion reading from the Psalms and found "traced in characters of light":

"You are my son and my beloved; I have chosen you for myself"

- with Jesus then claiming:

"today the word of God is fulfilled in the son of man".[33]

In Egypt[edit]

During the stay in Egypt, several miracles were reported;[when?] Jesus at nine months old explains Muslim creed fundamentals to a schoolmaster; Jesus reveals thieves to a wealthy chief; fills empty jars of something to drink; reveals what parents were eating at home while playing with their children; provides food and wine for a tyrannical king; proves to this same king his power in raising a dead man from the dead; raises a child accidentally killed; and causes the garments from a single-colored vat to come out with various colors.[13]

Adulthood[edit]

Mission[edit]

It is generally agreed that Jesus spoke Aramaic, the common language of Judea in the first century AD and the region at-large.[35]

Most Islamic tradition conveys Jesus and his teaching conformed to the prophetic model: a human, as with previous prophets, sent by God to a certain people at a certain time, to present both a judgement upon humanity for worshipping idols and a challenge to turn to the one true God. Tradition believes Jesus' mission was to the people of Israel, his status as a prophet confirmed by numerous miracles.[36]

The first and earliest view of Jesus in Islamic thought is that of a prophet; a human being chosen by God to present both a judgement upon humanity for worshipping idols and a challenge to turn to the one, true God, is foundational for all Muslims. From this basis reflected upon all previous prophets through the lens of Muslim identity, Jesus is no more than a messenger repeating the same message of the ages. Jesus is not traditionally perceived as divine, yet Muslim ideology is careful not to view Jesus as less than this, for in doing so would be sacrilegious and similar to rejecting a recognized Islamic prophet. The miracles of Jesus and the Quranic titles attributed to Jesus demonstrate the power of God rather than the divinity of Jesus—the same power behind the message of all prophets.[37]

A second early image of Jesus is an end-time figure, arising mostly from the Hadith. Muslim tradition constructs a narrative similar to found in Christian theology, seeing Jesus awaiting the end of time when he will descend to the earth and fight the Antichrist, championing the cause of Islam, when after doing so he will point to the primacy of Muhammad and die a natural death.[38]

A third and distinctive image is of Jesus representing an ascetic figure; a prophet of the heart. Although the Quran refers to the ‘gospel’ of Jesus, those specific teachings of his are not mentioned. The Sufi movement is where Jesus became revered, acknowledged as a spiritual teacher with a distinctive voice from other prophets, including Muhammad. Sufism is a tendency, within Islam, to explore the dimensions of union with God through many approaches including asceticism, poetry, philosophy, speculative suggestion and mystical methods. Although Sufism to the western mind may seem to share similar origins or elements of Neoplatonism, Gnosticism and Buddhism, the ideology is distinctly Islamic since they adhere to the words of the Quran and pursue imitation of Muhammad as the perfect man.[39]

Preaching[edit]

The Islamic concept of Jesus' preaching is believed to have originated in Kufa, Iraq, where the earliest writers of Muslim tradition and scholarship was formulated, whom the Kufan, are labeled after. The concepts of Jesus and his preaching ministry was adopted from the early ascetic Christians of Egypt who opposed official church bishopric appointments from Rome.[40]

The earliest stories numbering about 85 are found in two major collections of ascetic literature entitled Kitab al-Zuhd wa'l Raqa'iq (The Book of the Asceticism and Tender Mercies) by Ibn al-Mubarak (d. 797), and Kitab al-Zuhd (The Book of Asceticism) by Ibn Hanbal (d. 855). These sayings fall into four basic groups consisting of a) eschatological sayings; b) quasi-Gospel sayings; c) ascetic sayings and stories; d) sayings echoing intra-Muslim polemics.[41]

The first group of sayings expand Jesus' archetype as portrayed in the Quran. The second group of stories, although containing a Gospel core, are expanded with a "distinctly Islamic stamp". The third group, being the largest of the four, portrays Jesus as a patron saint of Muslim asceticism. The last group builds upon the Islamic archetype and Muslim-centric definition of Jesus and his attributes, furthering esoteric ideas regarding terms such as "Spirit of God" and "Word of God".[42]

Miracles[edit]

Miracles were attributed to Jesus as signs of his prophethood and his authority. Six miracles are specifically mentioned in the Quran, with these six initial miracle narratives being elaborated on over the centuries through Hadith and poetry.[citation needed]

Speaking from the cradle[edit]

One of the miracles mentioned in the Quran is that Jesus, while still in the cradle, spoke out to protect his mother Mary from any accusations people may have placed on her due to having a child without a father. When she was approached about this strange incident after her childbirth, Mary merely pointed to Jesus, and he miraculously spoke, just as God had promised her upon annunciation.

"He shall speak to people while still in the cradle, and in manhood, and he shall be from the righteous."

— Quran surah 3 (Al-Imran) ayah[citation needed] 46

This miracle is not found in the Bible, but it is found in the non-canonical Syriac Infancy Gospel. "He has said that Jesus spoke, and, indeed, when he was lying in his cradle, said to Mary, his mother: "I am Jesus, the Son of God, the Logos, whom thou hast brought forth, as the Angel Gabriel announced to thee; and my Father has sent me for the salvation of the world."[43]

Healing the blind and the leper[edit]

Similar to the New Testament, The Quran also mentions Jesus to have healed the blind and the lepers.

"I also heal the blind and the leper."

— Quran surah 3 (Al Imran) ayah[citation needed] 49

Creating birds from clay[edit]

God mentions a miracle given to none other in the Quran but Jesus, one which is quite parallel to how God himself created Adam. This miracle was one which none can argue its greatness. God mentions in the Quran that Jesus says:

"I create for you out of clay the likeness of a bird, then I breathe into it and it becomes a bird with God's permission."

— Quran surah 3 (Al Imran) ayah[citation needed] 49

This miracle is not found in the New Testament, but it is found in the non-canonical Infancy Gospel of Thomas; "When this boy, Jesus, was five years old, he was playing at the ford of a rushing stream. He then made soft clay and shaped it into twelve sparrows; Jesus simply clapped his hands and shouted to the sparrows: "Be off, fly away, and remember me, you who are now alive!" And the sparrows took off and flew away noisily."[citation needed]

Power over death[edit]

"...and I bring to life the dead, by the permission of God."

— Quran surah 3 (Al Imran) ayah[citation needed] 49

This, like the creation of a bird, was a miracle of incomparable nature, one that should have caused the Jews to believe in the prophethood of Jesus without any doubt. Islam agrees with Christianity that Jesus brought people back from the dead. The first three accounts are mentioned in both Islam and the Bible, save the last, which is only mentioned in Islam.

Prescience[edit]

Jesus has the miracle of prescience, or foreknowledge,[44] of what was hidden or unknown by others. One example is Jesus would answer any and every question anyone asked him correctly. Another example is Jesus knew what people had just eaten, as well as what they stored up in their houses.[13]

"I inform you too of what things you eat, and what you store up in your houses. Surely in that is a sign for you, if you are believers."

Tabari relates on the authority of Ibn Ishaq that when Jesus was about nine or ten years old, his mother Mary would send him to a Jewish religious school. But whenever the teacher tried to teach him anything, he found that Jesus already knew it. The teacher exclaimed, "Do you not marvel at the son of this widow? Every time I teach him anything, I find that he knows it far better than I do!" Tabari further relates on the authority of Ismail al-Suddi that "when Jesus was in his youth, his mother committed him [to the priests] to study the Torah. While Jesus played with the youths of his village, he used to tell them what their parents were doing." Sa'id ibn Jubayr, according to Tabari, is said to have reported that Jesus would say to one of his fellow playmates in the religious school, "Your parents have kept such and such food for you, would you give me some of it?" Jesus would usually tell his fellow pupils in the religious school what their parents ate and what they have kept for them when they return home. He used to say to one boy, "Go home, for your parents have kept for you such and such food and they are now eating such and such food."[13]

As parents became annoyed by this, they forbade their children to play with Jesus, saying, "Do not play with that magician." As a result, Jesus had no friends to play with and became lonely. Finally, the parents gathered all the children in a house away from Jesus. When Jesus came looking for them, the parents told Jesus that the children were not there. Jesus asked, "Then who is in this house?" The parents replied, "Swine!" (referring to Jesus). Jesus then said, "OK. Let there be swine in this house!" When the parents opened the door to the room where the children were, they found all their children had turned to swine, just as Jesus said.[45]

Tabari cites the Quran in support of this story:

"Those of the children of Israel who have rejected faith were cursed by the tongue of David and Jesus, son of Mary, this because of their rebellion and the acts of transgression which they had committed."

— Quran surah 5 (Al-Ma'ida) ayah[citation needed] 78

Table of food from heaven[edit]

In the fifth chapter of the Quran, God narrates how the disciples of Jesus requested him to ask God to send down a table laden with food, and for it to be a special day of commemoration for them in the future.[citation needed]

"When the disciples said: O Jesus, son of Mary! Is your Lord able to send down for us a table spread with food from heaven? He said: Observe your duty to God, if ye are true believers. They said: We desire to eat of it and our hearts be at rest, and that We may know that you have spoken truth to us, and that We may be witnesses thereof. Jesus, son of Mary, said: 'O God, our Lord, send down for us a table laden with food out of heaven, that shall be for us a recurring festival, the first and last of us, and a miracle from You. And provide us our sustenance, for You are the best of providers!"

— Quran surah 5 (Al-Ma'ida) ayah[citation needed] 112-114

Other miracles[edit]

Similar to the New Testament, Al-Tabari (d. 923) reports a story of Jesus's encounter with a certain King in the region. The identity of the King is not mentioned while legend suggests Philip the Tetrarch. The corresponding Bible reference is "the royal official's son." With regard to the reason which led Jesus to seek the support of the disciples in Islamic theology, al-Tabari relates the tale on the authority of As-Suddi.[46]

Another legendary miraculous story has to do with a Jewish man and loafs of bread. A lesson on greed and truth-telling is weaved into the narration.[47]

Scripture[edit]

Muslims believe that God revealed to Jesus a new scripture, al-Injīl (the Gospel), while also declaring the truth of the previous revelations: al-Tawrat (the Torah) and al-Zabur (the Psalms). The Quran speaks favorably of al-Injīl, which it describes as a scripture that fills the hearts of its followers with meekness and piety. The Quran says that the original biblical message has been distorted or corrupted (tahrif) over time.[citation needed] In chapter 3, verse 3, and chapter 5, verses 46-47, of the Quran, the revelation of al-Injil is mentioned.

Disciples[edit]

The Quran states that Jesus was aided by a group of disciples who believed in His message. While not naming the disciples, the Quran does give a few instances of Jesus preaching the message to them. According to Christianity, the names of the twelve disciples were Peter, Andrew, James, John, Philip, Bartholomew, Thomas, Matthew, James, Jude, Simon and Judas.

The Quran mentions in chapter 3, verses 52-53, that the disciples submitted to the faith of Islam:[non-primary source needed]

When Jesus found Unbelief on their part He said: "Who will be My helpers to (the work of) Allah?" Said the disciples: "We are Allah's helpers: We believe in Allah, and do thou bear witness that we are Muslims.

Our Lord! we believe in what Thou hast revealed, and we follow the Messenger; then write us down among those who bear witness."— Quran Surah Al-Imran 52-53[48]

The longest narrative involving Jesus' disciples is when they request a laden table to be sent from Heaven, for further proof that Jesus is preaching the true message:

Behold! the disciples, said: "O Jesus the son of Mary! can thy Lord send down to us a table set (with viands) from heaven?" Said Jesus: "Fear Allah, if ye have faith."

They said: "We only wish to eat thereof and satisfy our hearts, and to know that thou hast indeed told us the truth; and that we ourselves may be witnesses to the miracle."

Said Jesus, the son of Mary: "O Allah our Lord! Send us from heaven a table set (with viands), that there may be for us—for the first and the last of us—a solemn festival and a sign from thee; and provide for our sustenance, for thou art the best Sustainer (of our needs)."

Allah said: "I will send it down unto you: But if any of you after that resisteth faith, I will punish him with a penalty such as I have not inflicted on any one among all the peoples."— Quran Surah Al-Ma'ida 112-115[49]

Death[edit]

Most Islamic traditions, save for a few, categorically deny that Jesus physically died, either on a cross or another manner. The contention is found within the Islamic traditions themselves, with the earliest Hadith reports quoting the companions of Muhammad stating Jesus having died, while the majority of subsequent Hadith and Tafsir have elaborated an argument in favor of the denial through exegesis and apologetics, becoming the popular (orthodox) view.

Professor and scholar Mahmoud M. Ayoub sums up what the Quran states despite interpretative arguments:

"The Quran, as we have already argued, does not deny the death of Christ. Rather, it challenges human beings who in their folly have deluded themselves into believing that they would vanquish the divine Word, Jesus Christ the Messenger of God. The death of Jesus is asserted several times and in various contexts." (3:55; 5:117; 19:33.)[50]

Some disagreement and discord can be seen beginning with Ibn Ishaq's (d. 761) report of a brief accounting of events leading up to the crucifixion, firstly stating that Jesus was replaced by someone named Sergius, while secondly reporting an account of Jesus' tomb being located at Medina and thirdly citing the places in the Quran (3:55; 4:158) that God took Jesus up to himself.[51]

An early interpretation of verse 3:55 (specifically "I will cause you to die and raise you to myself"), Al-Tabari (d. 923) records an interpretation attributed to Ibn 'Abbas, who used the literal "I will cause you to die" (mumayyitu-ka) in place of the metaphorical mutawaffi-ka "Jesus died", while Wahb ibn Munabbih, an early Jewish convert, is reported to have said "God caused Jesus, son of Mary, to die for three hours during the day, then took him up to himself." Tabari further transmits from Ibn Ishaq: "God caused Jesus to die for seven hours",[52] while at another place reported that a person called Sergius was crucified in place of Jesus. Ibn-al-Athir forwarded the report that it was Judas, the betrayer, while also mentioning the possibility it was a man named Natlianus.[53]

Al-Masudi (d. 956) reported the death of Christ under Tiberius.[53]

Ibn Kathir (d. 1373) follows traditions which suggest that a crucifixion did occur, but not with Jesus.[54] After the event, Ibn Kathir reports the people were divided into three groups following three different narratives; The Jacobites believing ‘God remained with us as long as He willed and then He ascended to Heaven;’ The Nestorians believing ‘The son of God was with us as long as he willed until God raised him to heaven;’ and the Muslims believing; ‘The servant and messenger of God, Jesus, remained with us as long as God willed until God raised him to Himself.’[55]

Another report from Ibn Kathir quotes Ishaq Ibn Bishr, on authority of Idris, on authority of Wahb ibn Munabbih, that "God caused him to die for three days, then resurrected him, then raised him."[56][57]

Quranic commentators seem to have concluded the denial of the crucifixion of Jesus by following material interpreted in Tafsir that relied upon extra-biblical Judeo-Christian sources, venturing away from the message conveyed in the Quran,[58] with the earliest textual evidence having originated from a non-Muslim source; a misreading of the Christian writings of John of Damascus regarding the literal understandings of Docetism (exegetical doctrine describing spiritual and physical realities of Jesus as understood by men in logical terms) as opposed to their figurative explanations.[59] John of Damascus highlighted the Quran's assertion that the Jews did not crucify Jesus being very different from saying that Jesus was not crucified, explaining that it is the varied Quranic exegetes in Tafsir, and not the Quran itself, that denies the crucifixion, further stating that the message in the 4:157 verse simply affirms the historicity of the event.[60]

Ja’far ibn Mansur al-Yaman (d. 958), Abu Hatim Ahmad ibn Hamdan al-Razi (d. 935), Abu Yaqub al-Sijistani (d. 971), Mu'ayyad fi'l-Din al-Shirazi (d. 1078) and the group Ikhwan al-Safa also affirm the historicity of the Crucifixion, reporting Jesus was crucified and not substituted by another man as maintained by many other popular Quranic commentators and Tafsir.

In reference to the Quranic quote "We have surely killed Jesus the Christ, son of Mary, the apostle of God", Muslim scholar Mahmoud Ayoub asserts this boast not as the repeating of a historical lie or the perpetuating of a false report, but an example of human arrogance and folly with an attitude of contempt towards God and His messenger(s). Ayoub furthers what modern scholars of Islam interpret regarding the historical death of Jesus, the man, as man's inability to kill off God's Word and the Spirit of God, which the Quran testifies were embodied in Jesus Christ. Ayoub continues highlighting the denial of the killing of Jesus as God denying men such power to vanquish and destroy the divine Word. The words, "they did not kill him, nor did they crucify him" speaks to the profound events of ephemeral human history, exposing mankind's heart and conscience towards God's will. The claim of humanity to have this power against God is illusory. "They did not slay him...but it seemed so to them" speaks to the imaginations of mankind, not the denial of the actual event of Jesus dying physically on the cross.[61]

Islamic reformer Muhammad Rashid Rida agrees with contemporary commentators interpreting the physical killing of Christ's apostleship as a metaphorical interpretation.[62]

Substitution[edit]

It is unclear exactly where the substitutionist interpretation originated, but some scholars consider the theory originating among certain heretical Gnostic groups of the second century.[30]

Leirvik finds the Quran and Hadith to have been clearly influenced by the non-canonical ('heretical') Christianity that prevailed in the Arab peninsula and further in Abyssinia.[63]

Muslim commentators have been unable to convincingly disprove the crucifixion. Rather, the problem has been compounded by adding the conclusion of their substitutionist theories. The problem has been one of understanding.[64]

"If the substitutionist interpretation (Christ replaced on the cross) is taken as a valid reading of the Qur'anic text, the question arises of whether this idea is represented in Christian sources. According to Irenaeus' Adversus Haereses, the Egyptian Gnostic Christian Basilides (2nd century) held the view that Christ (the divine nous, intelligence) was not crucified, but was replaced by Simon of Cyrene. However, both Clement of Alexandria and Hippolytus denied that Basilides held this view. But the substitutionist idea in general form is quite clearly expressed in the Gnostic Nag Hammadi documents Apocalypse of Peter and The Second Treatise of the Great Seth."[51]

While most western scholars,[65] Jews,[66] and Christians believe Jesus died, orthodox Muslim theology teaches he ascended to Heaven without being put on the cross and God transformed another person, Simon of Cyrene, to appear exactly like Jesus who was crucified instead of Jesus (cf. Irenaeus' description of the heresy of Basilides, Book I, ch. XXIV, 4.).[67]

Ascension[edit]

Modern Islamic scholars like Sayyid Muhammad Husayn Tabataba'i interpret the ascension of Jesus as spiritual, not physical. This interpretation is in accord with Muʿtazila and Shia metaphorical explanations regarding anthropomorphic references to God in the Quran. Although not popular with traditional Sunni interpretations of the depiction of crucifixion, there has been much speculation and discussion in the effort of logically reconciling this topic.[68]

In ascetic Shia writings, Jesus is depicted having "ascended to heaven wearing a woolen shirt, spun and sewed by Mary, his mother. As he reached the heavenly regions, he was addressed, “O Jesus, cast away from you the adornment of the world."[69]

Second coming[edit]

According to Islamic tradition which describes this graphically, Jesus' descent will be in the midst of wars fought by al-Mahdi (lit. "the rightly guided one"), known in Islamic eschatology as the redeemer of Islam, against al-Masīh ad-Dajjāl (the Antichrist "false messiah") and his followers.[70] Jesus will descend at the point of a white arcade, east of Damascus, dressed in yellow robes—his head anointed. He will say prayer behind al-Mahdi then join him in his war against the Dajjal. Jesus, considered as a Muslim, will abide by the Islamic teachings. Eventually, Jesus will slay the Antichrist, and then everyone who is one of the People of the Book (ahl al-kitāb, referring to Jews and Christians) will believe in him. Thus, there will be one community, that of Islam.[71][72][non-primary source needed]

Sahih al-Bukhari, Volume 3, Book 43: Kitab-ul-`Ilm (Book of Knowledge), Hâdith Number 656:

Allah's Apostle said, "The Hour will not be established until the son of Mary (i.e. Jesus) descends amongst you as a just ruler, he will break the cross, kill the pigs, and abolish the Jizya tax. Money will be in abundance so that nobody will accept it (as charitable gifts)."

— Narrated by Abu Huraira[73][non-primary source needed]

After the death of al-Mahdi, Jesus will assume leadership. This is a time associated in Islamic narrative with universal peace and justice. Islamic texts also allude to the appearance of Ya'juj and Ma'juj (known also as Gog and Magog), ancient tribes which will disperse and cause disturbance on earth. God, in response to Jesus' prayers, will kill them by sending a type of worm in the napes of their necks.[70] Jesus' rule is said to be around forty years, after which he will die. Muslims will then perform the funeral prayer for him and then bury him in the city of Medina in a grave left vacant beside Muhammad, Abu Bakr, and Umar (companions of Muhammad and the first and second Sunni caliphs (Rashidun) respectively.[74]

In Islamic theology[edit]

Jesus is described by various means in the Quran. The most common reference to Jesus occurs in the form of Ibn Maryam (son of Mary), sometimes preceded with another title. Jesus is also recognized as a nabī (prophet) and rasūl (messenger) of God. The terms `abd-Allāh (servant of God), wadjih ("worthy of esteem in this world and the next") and mubārak ("blessed", or "a source of benefit for others") are all used in reference to him.[74]

Islam sees Jesus as human only, sent as the last prophet of Israel to Jews with the Gospel scripture.[76][77] It rejects any divine notions of being God, begotten Son of God and the Trinity as a whole; according to theologians such beliefs constitute Shirk (the "association" of partners with God) and thereby a rejection of his divine oneness (tawhid) as the sole unpardonable sin.[78] These doctrinal origins are ascribed to Paul the Apostle who is regarded as a false heretic,[79] as well as an evolution across the Greco-Roman world causing pagan influences to corrupt God's revelation.[80] Therefore, the theological absence of Original Sin in Islam renders the Christian concepts of Atonement and Redemption as redundant. Jesus is simply reflected upon as a figure who conforms to the prophetic model of his predecessors.[36]

He is understood as to have preached salvation through submission to God's will and worshipping him alone, and ultimately denies being a divine claimant.[81] Thus, he is considered to have been a Muslim by the definition of the term (i.e., one who submits to God's will), as were all other prophets that preceded him.[82] A comprehensive verse reads:

O People of the Scripture! Do not exaggerate in your religion nor utter aught concerning Allah save the truth. The Messiah, Jesus son of Mary, was only a messenger of Allah, and His word which He conveyed unto Mary, and a spirit from Him. So believe in Allah and His messengers, and say not "Three" - Cease! better for you! - Allah is only One Allah. Far is it removed from His Transcendent Majesty that He should have a son. His is all that is in the heavens and all that is in the earth. And Allah is sufficient as Defender.

— Quran sura 4 (An-Nisa), ayah 171[83]

A frequent title of Jesus mentioned is al-Masīḥ, which translates to "the Messiah", as well as Christ. Although the Quran is silent on its significance,[84] scholars disagree with the Christian concepts of the term, and lean towards a Jewish understanding. Muslim exegetes explain the use of the word masīh in the Quran as referring to Jesus' status as the one anointed by means of blessings and honors; or as the one who helped cure the sick, by anointing the eyes of the blind, for example.[74]

Jesus also holds a description from God as both a word and a spirit. Quranic verses assert that he is a Word from God, which is interpreted as a reference to the creating Word uttered at the moment of his conception, and identified as "Be".[85] Jesus is thus God's Word in a causal sense as his existence came through it, rather than being a manifestation of the Word itself, and hence differing from the Christian Logos.[86]

The interpretation behind Jesus as a spirit from God, is seen as his human soul.[86] Some Muslim scholars occasionally see the spirit as the archangel Gabriel, but majority consider the spirit to be Jesus himself.[87]

Similitude with Adam[edit]

The Quran emphasises the creationism of Jesus, through his similitude with Adam in regards to an absence of divine intervention.

Indeed, the example of Jesus to Allah is like that of Adam. He created Him from dust; then He said to him, "Be," and he was.

— Quran sura 3 (Ali 'Imran), ayah 59[88]

Islamic exegesis extrapolates a logical inconsistency behind the Christian argument, as such implications would have ascribed divinity to Adam who is understood as creation only.[84][89] Adam likewise was both created through the Word of God and described as a spirit from him.[86] Furthermore, their equation is also depicted numerically, as both Adam and Jesus are referred to by name 25 times each.[90]

Precursor to Muhammad[edit]

| Lineage of several prophets according to Islamic tradition |

|---|

| Dotted lines indicate multiple generations |

The tree shown right depicts lineage. Muslims believe that Jesus was a precursor to Muhammad, and that he announced the latter's coming. They base this on a verse of the Quran wherein Jesus speaks of a messenger to appear after him named Ahmad.[91][citation needed] Islam associates Ahmad with Muhammad, both words deriving from the h-m-d triconsonantal root which refers to praiseworthiness. Muslims also assert that evidence of Jesus' pronouncement is present in the New Testament, citing the mention of the Paraclete whose coming is foretold in the Gospel of John.[92][citation needed]

Muslim theology states Jesus had predicted another Prophet succeeding him according to this message in the Quran which mentions:

And remember, Jesus, the son of Mary, said: "O Children of Israel! I am the apostle of God (sent) to you, confirming the Law (which came) before me, and giving glad tidings of a Messenger to come after me, whose name shall be Ahmad." But when he came to them with clear signs, they said, "this is evident sorcery!"

— Sura 61:6[citation needed]

(Ahmad is an Arabic name from the same triconsonantal root Ḥ-M-D = [ح - م - د].)

Muslim commentators claim that the original Greek word used was periklutos, meaning famed, illustrious, or praiseworthy—rendered in Arabic as Ahmad; and that this was replaced by Christians with parakletos.[74][93] Islamic scholars debate whether this traditional understanding is supported by the text of the Quran. Responding to Ibn Ishaq's biography of Muhammad, the Sirat Rasul Allah, Islamic scholar Alfred Guillaume wrote:

Coming back to the term "Ahmad", Muslims have suggested that Ahmad is the translation of periklutos, celebrated or the Praised One, which is a corruption of parakletos, the Paraclete of John XIV, XV and XVI.[94]

Messianism[edit]

An alternative, more esoteric, interpretation is expounded by Messianic Muslims[95][citation needed] in the Sufi and Isma'ili traditions so as to unite Islam, Christianity and Judaism into a single religious continuum.[96] Other Messianic Muslims hold a similar theological view regarding Jesus, without attempting to unite the religions.[97][98][99] Making use of the New Testament's distinguishing between Jesus, Son of Man (being the physical human Jesus), and Christ, Son of God (being the Holy Spirit of God residing in the body of Jesus), the Holy Spirit, being immortal and immaterial, is not subject to crucifixion — for it can never die, nor can it be touched by the earthly nails of the crucifixion, for it is a being of pure spirit. Thus, while the spirit of Christ avoided crucifixion by ascending unto God, the body that was Jesus was sacrificed on the cross, thereby bringing the Old Testament to final fulfillment. Thus Quranic passages on the death of Jesus affirm that while the Pharisees intended to destroy the Son of God completely, they, in fact, succeeded only in killing the Son of Man, being his nasut (material being). Meanwhile, the Son of God, being his lahut (spiritual being) remained alive and undying — because it is the Holy Spirit.[100]

In Islamic literature[edit]